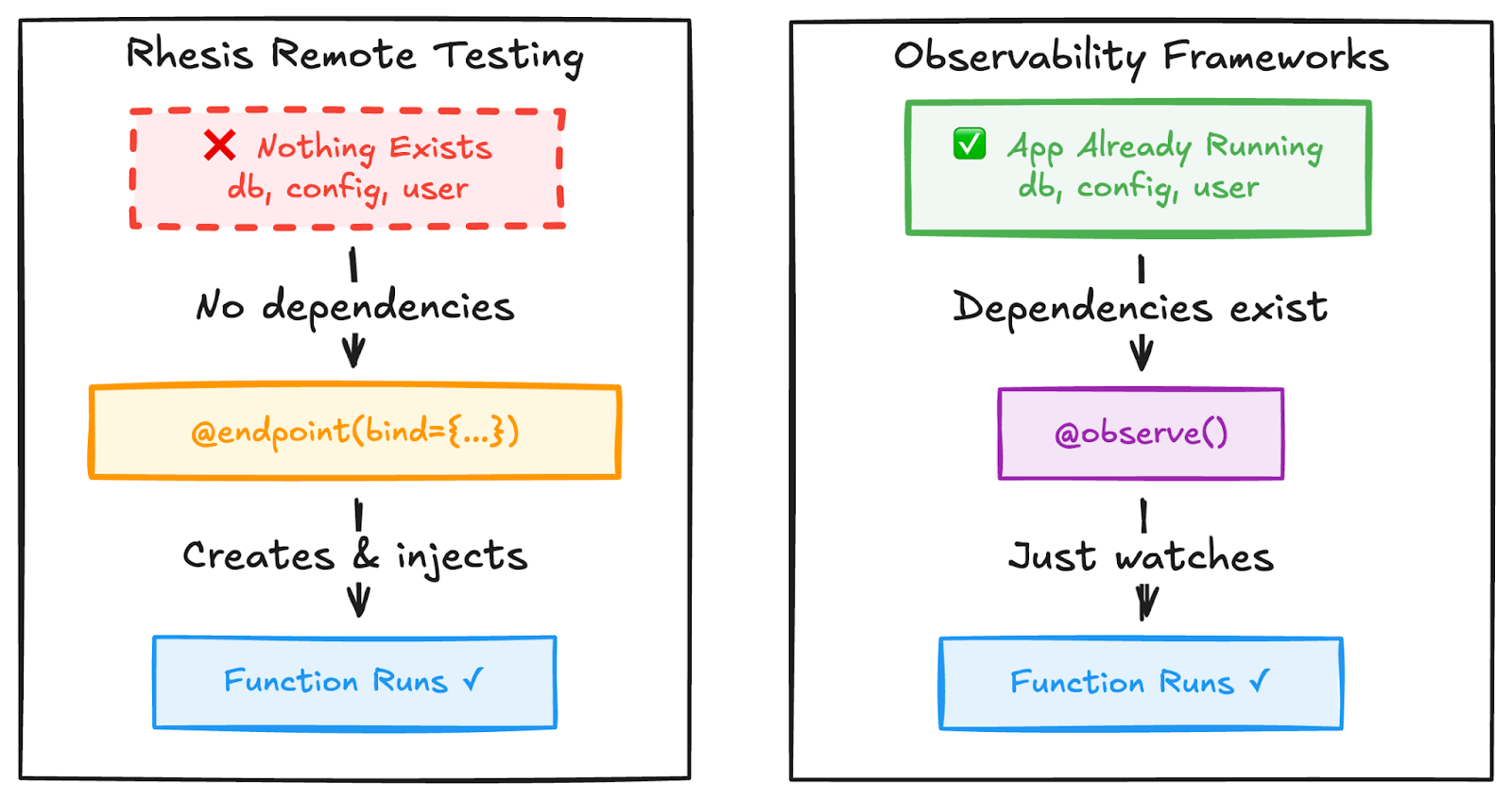

Observability frameworks wrap functions to monitor their execution. Rhesis also wraps functions for observability, but adds another feature: remote testing. In this blog post, we’ll explore why remote testing requires dependency binding while observability doesn’t, and how we solved this with the bind parameter.

When we started building the @endpoint decorator for Rhesis, we spent time studying how observability frameworks handle function instrumentation. Langfuse traces LLM calls and captures metadata with decorators like @observe(). TruLens evaluates LLM applications by wrapping components. PatronusAI tracks prompts and evaluates outputs. OpenTelemetry, the industry standard, instruments distributed systems with @trace() decorators.

These frameworks share a common approach: they observe the function already running with their dependencies in place. Timing, inputs, outputs, errors: everything is captured, but none of them create the context needed for execution.

Here's a real example from Langfuse's documentation:

Here, db is already initialized by the application, while Langfuse's decorator captures inputs, outputs, and metadata. The function runs in your application where db already exists. If this is a FastAPI endpoint, db came from Depends(). If it's a script, you initialized it at the top of the file. The function runs in its natural context, and Langfuse just watches.

In Rhesis, we also implemented a similar decorator: which is called @observe, just like in Langfuse, and it works the same way. But we also needed something more.

Rhesis has an additional requirement: test your LLM applications remotely. Unlike observability frameworks, which simply watch functions in their normal application context, Rhesis must be able to invoke them on demand from the testing platform (read more about remote testing here).

When you use @observe, the function works exactly like it does in other observability frameworks. Your application is running. Dependencies exist. The decorator just watches.

When you use @endpoint, the function needs to work in two contexts:

Your application invokes the function normally. FastAPI provides dependencies via Depends(),Flask via request context. Everything works like @observe.

Our test platform triggers the function via WebSocket. There’s no application framework, no HTTP request, and no dependency injection: just an isolated function missing the database, user context, and configuration it expects.

The @endpoint decorator solves this automatically: it registers your function as an endpoint with Rhesis, so the platform can trigger it remotely for testing while keeping it fully functional locally.

Consider this function:

In local execution, these functions work: your application framework provides the context. In remote testing, they fail: no context exists. This is a problem observability frameworks never face.

Observability frameworks observe functions with existing dependencies. Rhesis must create them for remote execution

We researched how observability frameworks handle this. The answer: they don't, because they don't need to.

Langfuse provides decorators like @observe() that wrap existing functions. Their decorator documentation shows they capture metadata from functions that are already executing. If your function needs a database, you've already figured out how to get one before calling the LLM. Langfuse watches.

OpenTelemetry traces requests as they flow through your production system. Their Python instrumentation guide shows decorators like @trace() that instrument the execution path. The request brings all the context. Database connections. Auth tokens. Configuration. OpenTelemetry instruments without manufacturing dependencies.

TruLens uses function wrapping to evaluate LLM applications. Their approach assumes your application is already running with all necessary context. They wrap components to analyze behavior, not to provide dependencies.

PatronusAI focuses on evaluation of LLM outputs from production traffic or test harnesses you've already built. Their evaluation framework analyzes results rather than invoking functions.

All of these frameworks don't face our problem because passive observation doesn't require dependency injection. They instrument code that's already running in a context where dependencies exist.

Rhesis's @observe works the same way. But our @endpoint decorator has a dual purpose: observability AND remote testing. The remote testing capability creates the dependency injection requirement.

Without a solution, developers face three uncomfortable options.

Global state

You could set up a DB_SESSION variable at module level, initialize it during app startup, and reference it in your decorated functions.

But this breaks isolation and testing, creates thread safety issues and per-request contexts like multi-tenancy and auth almost impossible.

Inline Creation

Now you're duplicating connection management everywhere, losing the benefits of dependency injection patterns you already use.

Pass everything as parameters:

You could pass everything as parameters. Make the database, config, and auth context explicit function arguments alongside actual business inputs. This pollutes the API signature. Remote callers would need to provide db, config, auth. They can't. They don't have these objects. The interface between business logic and infrastructure gets confused.

But this pollutes your API signature. Remote callers can't provide db or config: they don't have these objects. Your function is now mixing business logic with infrastructure concerns.

We added a bind parameter to the @endpoint decorator. The bind parameter declares dependencies that should be injected at call time while keeping them out of the remote signature.

The registry inspects the function signature and excludes bound parameters from the registered API schema. Remote callers only see user_id. When the function executes, whether locally or remotely, the decorator injects bound parameters into kwargs before calling the actual function.

The mental model stays consistent with what you already know. If you're using FastAPI's dependency injection:

Your Rhesis endpoint looks almost identical:

Static vs. Callable Bindings

You can bind static values like singletons (AppConfig()) or callables that evaluate at call time (lambda: get_db_session()).

The callable pattern matters for managing resource lifecycle:

Every invocation gets a fresh database session from the pool, uses it, cleans up. There are no shared states or connection leaks.

Separation of Concerns

Business logic parameters stay separate from infrastructure parameters:

Remote callers see: query_policy(user_id: str, policy_type: str = "term"). This is the actual API contract, free of infrastructure noise.

Testing with Mocks

Bound parameters can be overridden when passed explicitly:

Bound parameters can still be overridden when passed explicitly: useful for testing but transparent in production.

This pattern came directly from our users. They needed to query different databases based on tenant context:

Without binding, this would require passing org_id and user_id as parameters, even though they're environmental context. With binding, the function signature stays clean while the implementation gets what it needs.

Before and After

Consider the same function. Without binding, you face the uncomfortable choices from earlier:

With binding:

The second version is clearer and more maintainable. Remote callers see generate_response(user_query: str). Infrastructure dependencies are managed declaratively.

Before settling on the bind parameter, we explored several alternatives.

Reuse FastAPI's Depends(). We considered integrating with FastAPI's dependency injection system. FastAPI has elegant DI with Depends() that resolves dependencies at request time. The problem: it's tightly coupled to FastAPI's request lifecycle. Our decorated functions need to work outside HTTP request contexts. When triggered remotely via WebSocket, there's no request object, no dependency resolution context. We'd need to reimplement most of FastAPI's DI system anyway.

Use a dedicated DI framework. Python has DI frameworks like dependency-injector and injector. These are powerful but heavyweight. They require configuring containers, defining providers, managing scopes. Developers would need to learn an entire DI framework just to test their functions. The cognitive overhead didn't match the ergonomics we wanted.

Convention over configuration. We considered auto-detecting dependencies by name. If a parameter is named db, automatically inject a database session. If it's config, inject configuration. This works until it doesn't. What if someone needs two different database connections? What about testing with mocks? Implicit behavior makes debugging harder. Explicit is better than implicit.

Require manual wiring. We could have made developers write their own wrapper functions that inject dependencies, then decorate those. This pushes the problem onto users. They'd write boilerplate for every function. The whole point of the decorator is to reduce friction, not create more.

The bind parameter introduces complexity. Developers need to understand which parameters are injected and which come from callers. The decorator signature becomes more sophisticated. Function behavior depends on invisible dependencies that aren't in the signature.

We could have kept things simpler by requiring developers to manage dependencies themselves, by either using global state, creating connections inline or passing everything as parameters. Simpler decorator, more burden on users.

We chose to absorb complexity in the framework rather than push it onto every user. One well-designed parameter injection system serves thousands of developers. The alternative is thousands of developers each solving the same problem differently, with varying degrees of correctness and maintainability.

The trade-off makes sense because dependency injection is a solved problem in application frameworks. FastAPI has Depends(). Django has middleware. Flask has g. Developers already understand these patterns. We're not inventing a new concept, we're making a familiar pattern work in a context where it didn't exist before.

We borrowed heavily from observability frameworks. OpenTelemetry's semantic conventions show the value of standardized metadata. Langfuse's automatic parameter capture demonstrates elegant decorator design. TruLens's component wrapping shows how to instrument without invasiveness.

But we kept coming back to this question: if binding is useful, why doesn't it exist in other observability frameworks?

The answer is straightforward. Observability frameworks observe functions that are already running with dependencies already injected by your application framework. Langfuse wraps functions but doesn't invoke them. OpenTelemetry instruments code but doesn't trigger execution. They're passengers on a journey that's already happening: the application framework (FastAPI, Flask, Django) has already resolved dependencies, established database connections, and loaded configuration before the observability decorator ever sees the function.

Rhesis triggers functions remotely where no application framework has run. There's no FastAPI request that brought a database connection via Depends(), no Flask context with g.db, no Django middleware that set up the request user. We must solve dependency injection ourselves.

We're not smarter than the OpenTelemetry team. We have a different problem. Remote function invocation with real dependencies required a solution they never needed. Their choice to not include parameter injection wasn't an oversight. It was the right decision for their use case. Passive observation doesn't require dependency management.

Binding makes remote testing feel like first-class functionality. Your functions work the same way locally and remotely. Testing doesn't require refactoring your code. Dependencies are declared clearly and managed consistently. That's when a testing platform becomes something developers actually want to use.

We looked at how the industry handles observability, realized our problem was different, and built something new. The bind parameter is specific to Rhesis because remote function invocation with dependency injection is specific to what Rhesis does.

Other frameworks don't need it. We do. So we built it.

Ready to try it? Check out our Traces documentation to see binding in action and start testing your LLM applications with proper dependency injection today.