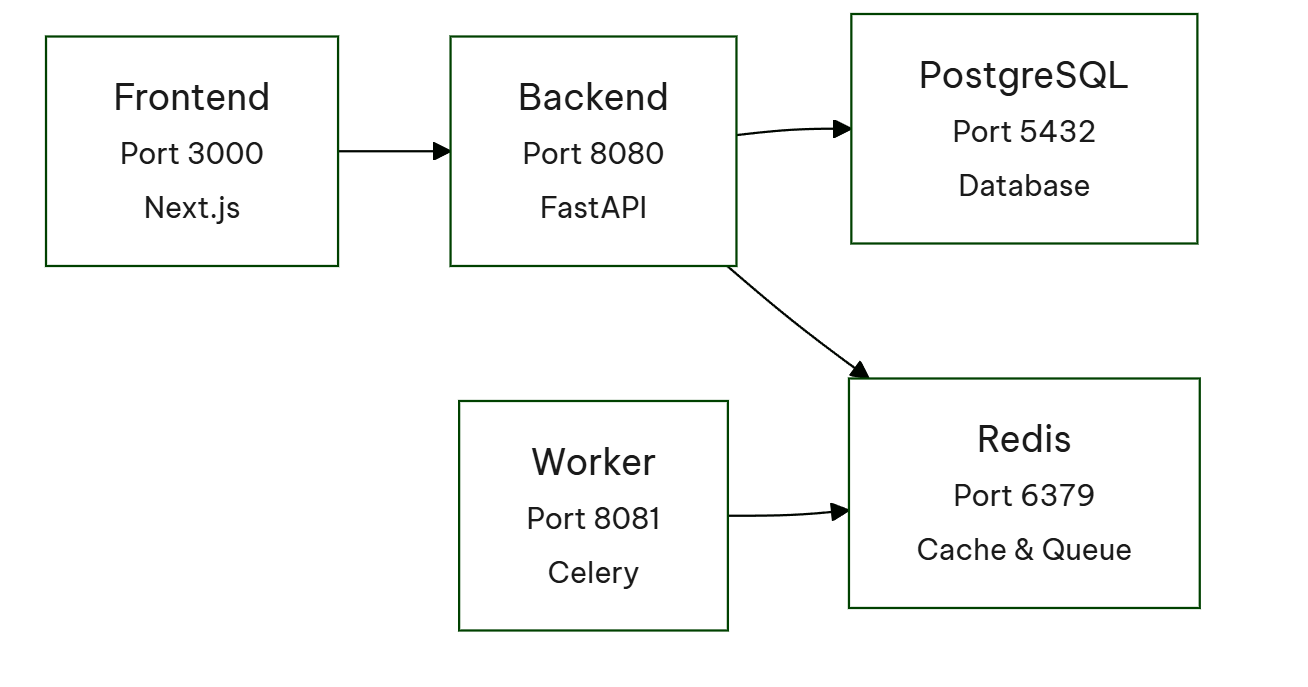

Our LLM testing solution features a typical architecture: a React-based frontend, a Python backend, and a Python-Celery worker for handling time-consuming tasks. Docker containers were the natural choice for deploying this stack. The application is available both on Google Cloud at app.rhesis.ai and for local self-hosting using Docker Compose (more details in this post). The image below provides an overview of the application’s components.

An initial review of the Docker images revealed two major issues: excessively long build times and image sizes that were far too large.The backend image, for instance, was nearly 6GB with a deployment time of approximately 15 minutes. The frontend was 3GB, taking about 10 minutes to deploy. These figures were clearly excessive and needed attention.

Bloated Docker images negatively impact the user experience, making it harder for new users to get started. Our objective is to allow users to clone our repository and start using Rhesis as quickly as possible.

My investigation began by identifying the cause of the excessively large layer sizes. The `docker history -H <image_name_or_id>` command, which reveals individual layer sizes, proved invaluable in this process.

One layer containing the following commands appeared particularly suspicious:

This layer not only added more than a minute to the build time but also contributed nearly 2GB to the image size in both the frontend and backend.

The root cause lies in how Docker handles layering. The `chown` operation effectively creates a complete copy of all files with the new ownership applied. Consequently, a 2GB file set results in a new, additional 2GB layer. Simply removing this specific `chown` layer immediately saved 2GB of image space and reduced the build time by almost a minute.

Interestingly, the chown layer, which caused the permission issues, was repeatedly proposed by the Cursor AI agent. I frequently use Cursor for chatting, asking for better solutions, and general assistance. Despite my repeated explanations that this layer leads to a bloated image, the Cursor agent consistently suggested it as an "effective way of building images" when addressing the permission problems.

Initially, our Docker images were straightforward, involving the installation of dependencies, environment setup, and then starting a server. However, as the application grew, this approach became sub-optimal because the final image contained many files only necessary for the build process, not for serving the application.

To address this, we transitioned to a two-stage build process:

For the frontend, we utilize an even more granular three-stage build:

Layer organization in Docker significantly impacts caching and build time. Caching is a powerful mechanism that reduces build time by reusing results from previous builds instead of rebuilding from scratch.

The extent of cache utilization depends on which layers have changed. If a change occurs in one of the initial layers of the Dockerfile (e.g., adding a dependency), it invalidates subsequent layers, triggering their rebuild. Conversely, a change in one of the final layers allows the preceding layers to be retrieved from the cache, minimizing the overall build time.

Therefore, the general principle for layer organization is to arrange them from the least frequently changing elements to the most frequently changing elements.

Consider the following example:

This is a simplified example that initially seems acceptable. We are copying the application and then installing it using uv sync. However, this is not the optimal strategy. The issue is that any code change invalidates the COPY . /app layer and all subsequent steps. This forces a re-installation (and re-download) of all dependencies. A superior approach exists:

This optimization strategy, illustrated with a Python example, leverages multiple uv sync commands to maximize layer caching.

First, we copy only the dependency definition files (pyproject.toml and uv.lock) and run uv sync to install all dependencies except the project itself. Next, we copy the remaining application code and run uv sync again.

The key benefit is that if only the application code changes, the dependency installation layer remains cached, preventing unnecessary reinstallation. Only the COPY . /app layer and the final project installation are invalidated.

This "dependencies first, then code" pattern is also applied to our frontend build process, as described in the multi-stage build documentation.

Optimizing Docker Images for the LLM Testing Framework

Our LLM testing framework relies on a variety of libraries, some of which are significantly larger than others. A key example is the optional functionality allowing users to employ Hugging Face models as an LLM "judge." However, this heavy dependency is not required in our Google Cloud production image. Hugging Face, specifically, requires PyTorch, which is a very large library when bundled with CUDA.

By making Hugging Face an optional dependency, we successfully decoupled this heavy requirement from our standard build, resulting in a substantial image size reduction of nearly 500MB.

Accelerating Docker Builds with uv and Cache Mounting

We utilize uv as our package manager due to its exceptional speed. While uv employs caching to limit package downloads locally, this benefit is lost inside a typical Docker build environment, where each new build often necessitates re-downloading packages, consequently slowing down the build process.

To mitigate this issue and leverage uv's caching capability within Docker, we can implement cache mounts. This modification allows uv to use previously cached packages, significantly reducing build times.

We identified that the excessive size of our Docker images was caused by the inclusion of the entire, nearly 1 GB node_modules directory. To optimize this, we adopted a standalone build mode. This targeted approach ensures that only essential dependencies are included, resulting in a significant reduction of the image size to around 400 MB.

Similar improvements were made to our documentation portal, which also led to a reduction in both the image size and the build time.

Our Docker image optimization efforts have yielded considerable results, leading to significantly smaller image sizes and quicker deployment.

Key Results Achieved:

Faster development cycles and conservation of GitHub runner resources are direct benefits of these improvements.

Key Strategies for Docker Image Optimization

We've compiled essential best practices for optimizing Docker images, which you can apply to your own applications:

docker history: Use this command to identify and address overly large or problematic layers, such as those created by extensive chown operations.builder stage for compilation and a leaner runner stage for the final application.node_modules, leading to a substantial decrease in the built application's size.