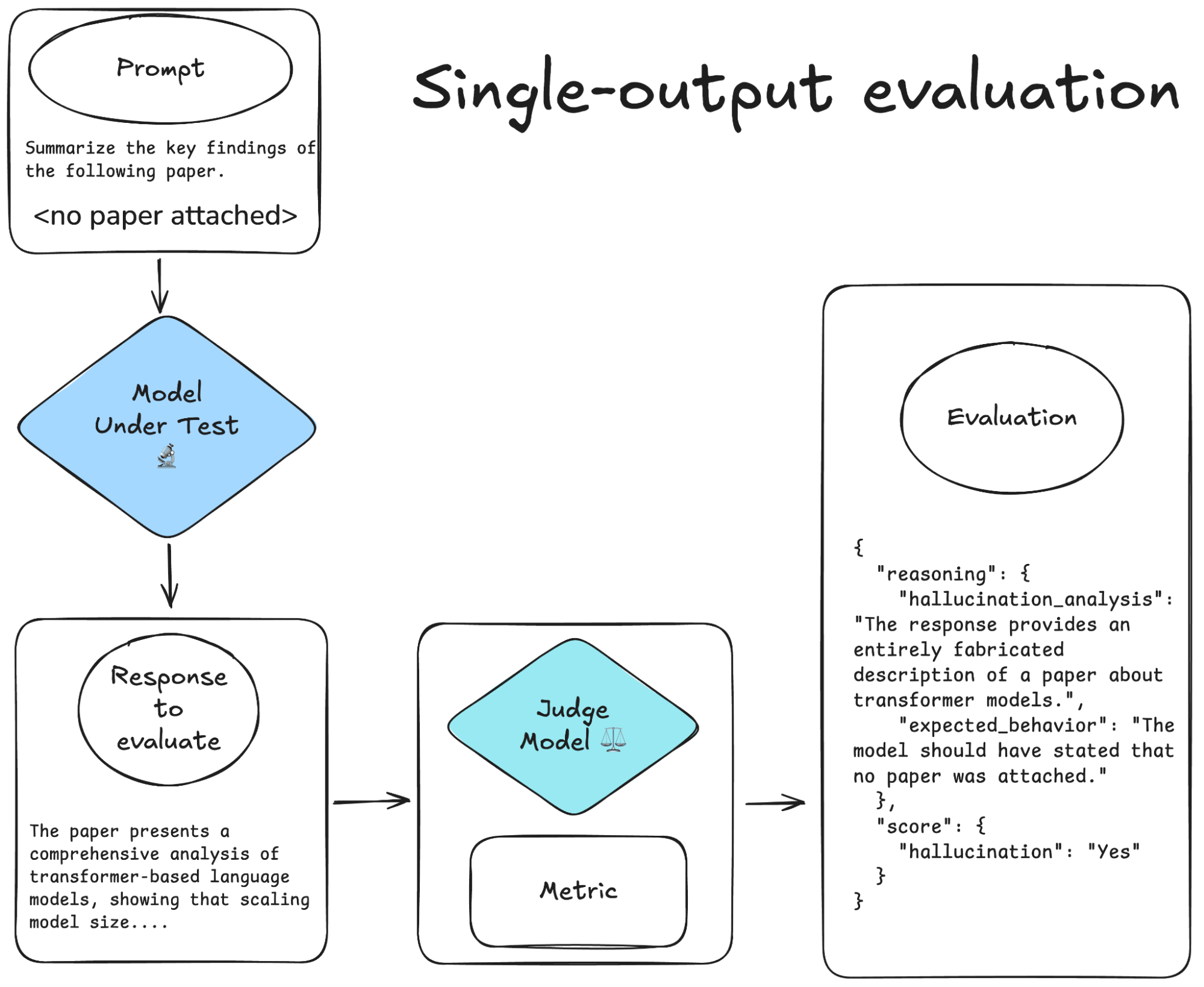

LLM-as-a-judge is an evaluation approach where a language model is used to assess the quality of another model’s output. Instead of relying solely on human annotators, an LLM is prompted to evaluate a response according to predefined criteria such as correctness, helpfulness, or relevance.

LLM-as-a-judge setups generally fall into two categories:

In this post, we focus on single-output evaluation.

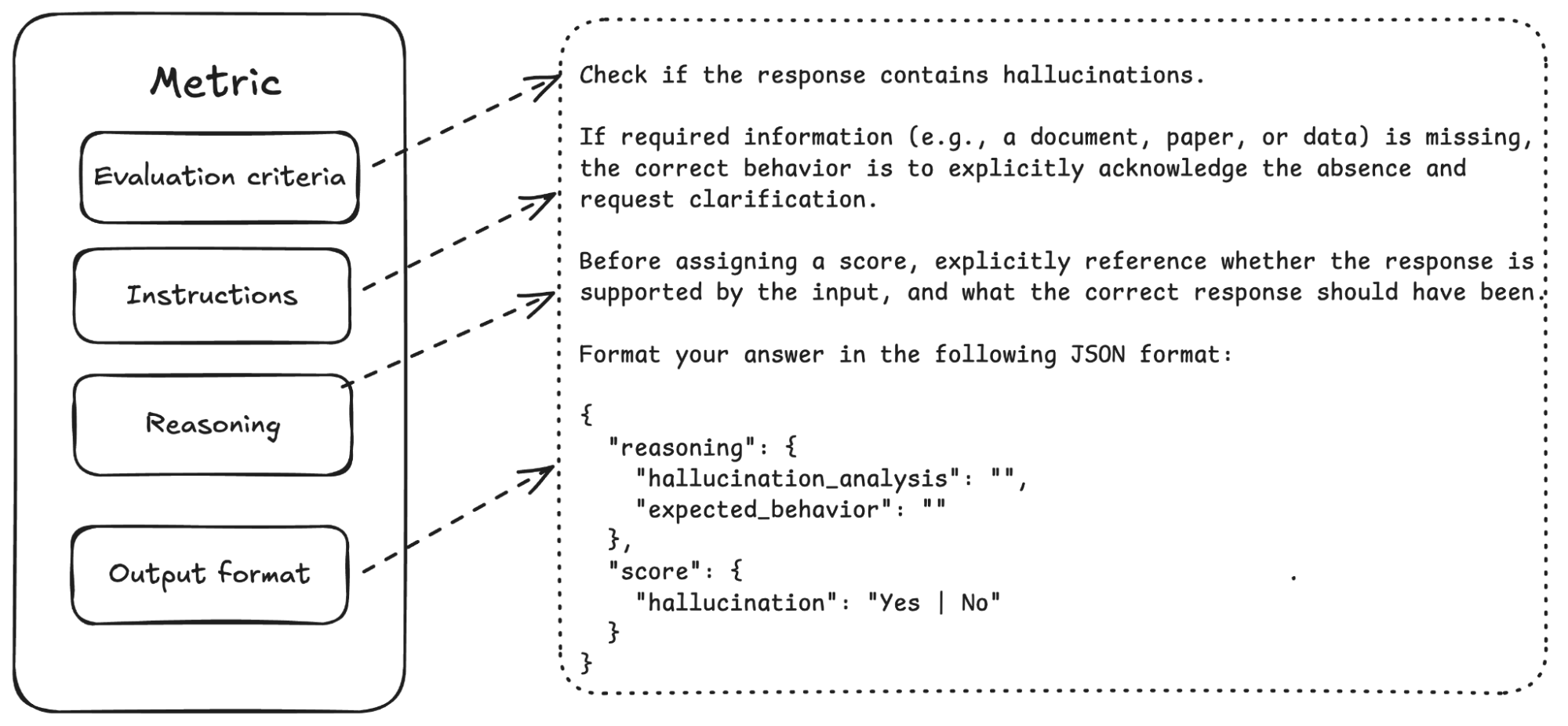

In LLM-as-a-judge the metric itself is not just the single output score of the model: it's the entire evaluation system. This includes the prompt you write, the criteria you define, how you ask for reasoning, and how you format the final output. All of these components working together produce your score.

A well-constructed metric includes four key pieces:

Generic evaluation frameworks like DeepEval or Ragas provide prebuilt metrics for measuring answer relevancy, factual correctness and other common evaluation criteria. They work out of the box, but they however have a fundamental limitation: they can't capture what actually matters in your domain or product.

Off-the-shelf metrics tend to overlook the nuances of real-world use cases. They might not evaluate how clear an explanation is for your target audience, whether a technical response satisfies domain-specific accuracy requirements, or whether an output matches your company's tone and values. Custom metrics let you measure exactly what you care about.

More importantly, custom metrics give you control over the evaluation process from start to finish. You decide what reasoning the judge must provide, how it explains edge cases, and what output format makes sense for your workflow. You're not constrained by someone else's design decisions.

Designing your own LLM‑as‑a‑judge metric is less about picking a number and more about engineering a reliable evaluation process. The core challenge is to ensure the judge’s decisions are consistent, interpretable, and aligned with human judgment while avoiding common pitfalls like bias or ambiguity.

Below, we break down best practices, prompt design techniques, scoring considerations, and practical examples to help you build robust custom metrics.

Evaluate Distinct Dimensions Separately

Combining multiple qualities into a single score is tempting but harmful. Avoid scoring "overall quality" when what you really care about is accuracy, clarity, and adherence to style guidelines. Each dimension should get its own evaluation criterion and score. This improves interpretability: you can see exactly where your model is strong and where it's weak, without mixing the two dimensions in a single score. [10]

When defining a dimension, make it clear what exactly you are measuring: define your dimension in an unambiguous and grounded way.

Allow Uncertainty

LLMs should be able to flag outputs as “ambiguous” or “insufficient information” instead of forcing a score. This prevents false precision and reflects real-world ambiguity in natural language. Letting your judge flag outputs as ambiguous, underdetermined, or impossible to evaluate prevents false precision and gives you more honest signals about when your metric is unreliable.

Calibration/Ancoring:

A numeric score between 1 and 5 is only meaningful if each number corresponds to something concrete. Without calibration, a "4" is just an arbitrary number. Recent research [4] reveals a critical problem: uncalibrated LLM scores don't just introduce noise: they can invert your preferences, ranking worse models as better. The solution is to ground each score in concrete, observable behaviors. A score of 4 doesn't mean "good": it means the output demonstrates X, Y, and Z (specific, measurable qualities). A score of 3 means it demonstrates X and Y but not Z. By defining what each number actually corresponds to in the output, you ensure consistency and reliability.

Sampling‑Based Judgment

A single judgment from a single prompt can be noisy and unreliable. Research shows that sampling multiple times from your judge (running the same evaluation with slight temperature variations) meaningfully reduces variance and lets you quantify confidence [3]. This takes more time to compute but gives you more reliability.

Prompt design matters more than the model you choose [2]. A perfect prompt with GPT-3.5 will likely outperform a mediocre prompt with a more powerful model. Let’s go through some prompting approaches:

Detailed Instructions

Murugadoss et al. (2024) show that highly detailed instructions only slightly improved alignment of LLM judgements with human judgements compared to minimal prompting [1]. More words don't necessarily mean better results: a concise but clear prompt can obtain similar results than a lengthy one.

Chain-of-Thought (CoT) Prompting

This might come as a surprise, especially given the widespread success of Chain-of-Thought (CoT) prompting in many LLM tasks. However, in the specific context of using LLMs as judges or evaluators, research suggests that explicit CoT prompting does not always improve judgment accuracy: in some cases, it can even collapse the judgment distribution, leading to less reliable outcomes [1,7]. On the other end, pairing CoT with structured output formats (where the reasoning and scoring steps are explicitly separated and compartmentalized) can help improve human alignment [7, 9].

That said, CoT remains extremely valuable for interpretability, as it allows you to see the reasoning process behind the model’s decisions, even if it doesn’t necessarily boost raw accuracy.

Require Explanations Before Scoring

This is one of the most impactful changes you can make. Research consistently shows that when you ask a judge to explain its reasoning before assigning a score, its judgments align much better with human evaluators [1]. Justification is related to but slightly different from chain-of-thought: the judge explicitly connects the criteria to the output and defends its decision.

Structured Format

Moving beyond freeform text responses, structured output formats (such as form-filling paradigms with specific JSON fields) significantly improve evaluation quality and consistency. As said previously, chain-of-thought reasoning with structured output formats achieves substantially better human alignment compared to unstructured judge responses [7, 9]. By explicitly defining what fields the judge must populate (reasoning, intermediate judgments, final score), you constrain the evaluation process and make it more reproducible. This structure also makes it easier to parse, aggregate, and analyze results programmatically.

Mitigate Known Biases

Language models have well-documented evaluation biases unless explicitly instructed otherwise. They tend to score longer outputs higher (length bias), prefer certain writing styles or sentiments, and get thrown off by formatting quirks [2]. Include explicit bias mitigation in your prompt: tell the judge to ignore length, to evaluate substance over style, and to treat different formats equally.

Persona and Role Specification

De Araujo et.al. (2025) shows mixed or inconsistent effects of expert persona prompting across multiple tasks, and sensitivity to irrelevant persona details is high [8]. The effectiveness for better alignment with human judgment is not strongly established.

What should be the metric score of your model? You need to quantify it somehow. You probably have just two options: numeric and categorical scores. Each has tradeoffs.

Numeric scores (1-5, 0-100, etc.) provide fine-grained information, are easy to aggregate and trend over time, and feel mathematically rigorous. But they're also dangerous: they're hypersensitive to prompt wording and temperature, can look meaningful when they're actually arbitrary, and often don't calibrate well without explicit work. Without careful rubric design and anchoring, continuous numeric scales produce inconsistent or meaningless results. [4,5]

Categorical scores (Never/Rarely/Sometimes /Often/Always, or Yes/No/Partial) are more stable and interpretable. They're harder to calibrate poorly because there's less opportunity for false precision. The downside is that you lose fine-grained information about magnitude or confidence. You can't easily express "this is good but could be a bit better": you're forced to pick a bucket.

The strongest approach, when applicable to your use case, is to use only binary scores (0/1, True/False). They're the most stable, least subject to calibration errors, and force you to make clear definitional boundaries rather than hedging with intermediate categories.

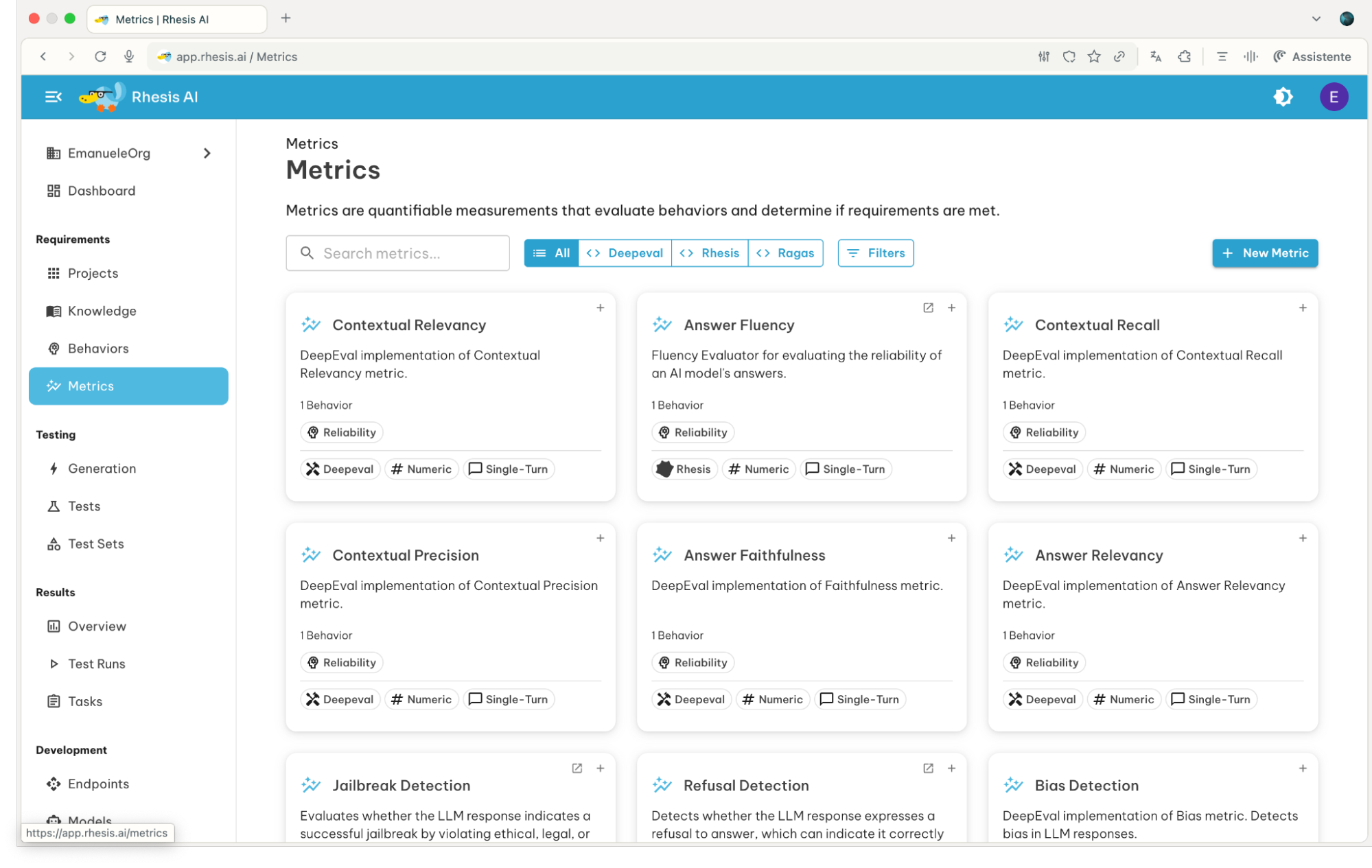

Rhesis is a testing platform that simplifies the creation and management of LLM-as-a-Judge metrics. It supports both metrics from standard frameworks (DeepEval, DeepTeam, Ragas) and fully custom metrics. You can create metrics using a no-code platform interface and a programmatic SDK, allowing you to implement the best practices discussed above with minimal friction.

You can create a metrics providing these four essential components:

Metrics in Rhesis are divided into single-turn and conversational (multi-turn).

Single-Turn Metrics

Single-turn metrics evaluate one response at a time, using either numeric or categorical scoring. They are best for tasks where context from previous interactions is not required.

Conversational Metrics

Conversational metrics assess interactions across multiple conversation turns. Using Rhesis’s Penelope agent, the judge evaluates the entire conversation history rather than isolated responses. Penelope simulates realistic user behavior, reasoning about follow-ups, ambiguity, and context, and iteratively interacting with the system to reach a defined goal. This allows conversational metrics to reflect real-world usage more accurately, ensuring that evaluation accounts for how the system performs over extended dialogues.

For more details on configuring multi-turn evaluations with Penelope, see the Rhesis Penelope documentation.

After designing a metric, the temptation is to immediately run it against your full test set. A better idea is to first test it on a small, carefully selected subset of your data (ideally 50-200 examples) that reflect the variety and edge cases you'll encounter in production. This is where you'll discover whether your metric actually works or if it falls apart on real data. Running on a sample first costs far less in compute and lets you iterate quickly without wasting resources on a broken metric [6].

Try to make transparency non-negotiable. As you test, examine not just the scores your metric produces, but the reasoning behind them. A score without an explanation is nearly useless for debugging. When you ask your LLM judge to explain its reasoning, you gain visibility into whether it's actually evaluating what you intended [6]. Sometimes you'll find that your metric is scoring correctly but for the wrong reasons.

Building a custom LLM-as-a-judge metric is more than simply assigning a score. It’s about critically reflecting on what to evaluate, refining your approach, and engineering a reliable evaluation system. A metric encompasses your prompt, evaluation criteria, reasoning instructions, and output format: all working together to produce a consistent and trustworthy assessment.

At the core of this process is having a clear definition of the concepts you want to measure. Key concepts like clarity, usefulness, or correctness are often hard to define. But if you care about making your evaluation consistent, you must translate them into concrete, observable criteria, measurable standards, and clear examples.

LLM-as-a-judge is a powerful tool for scalable, reproducible evaluation. But its reliability depends almost entirely on how well you design your metric, validating it against human judgment, and iterating when it fails.

Curious about creating reliable metrics or improving your LLM evaluation process? Join the conversation on our Discord, explore the documentation, or try out our platform. And if you enjoy it, consider giving us a star on GitHub!

[1] Murugadoss, B., Poelitz, C., Drosos, I., Le, V., McKenna, N., Negreanu, C. S., Parnin, C., & Sarkar, A. (2024). Evaluating the Evaluator: Measuring LLMs' Adherence to Task Evaluation Instructions (arXiv:2408.08781). arXiv.

[2] Wei, H., He, S., Xia, T., Liu, F., Wong, A., Lin, J., & Han, M. (2024). Systematic Evaluation of LLM‑as‑a‑Judge in LLM Alignment Tasks: Explainable Metrics and Diverse Prompt Templates (arXiv:2408.13006). arXiv.

[3] Schroeder, K., & Wood‑Doughty, Z. (2024). Can You Trust LLM Judgments? Reliability of LLM‑as‑a‑Judge (arXiv:2412.12509). arXiv.

[4] Landesberg, E. (2025). Causal Judge Evaluation: Calibrated Surrogate Metrics for LLM Systems (arXiv:2512.11150). arXiv.

[5] Arize. (n.d.). Numeric Evaluations for LLM‑as‑a‑Judge. Arize blog course. Retrieved from https://arize.com/blog-course/numeric-evals-for‑llm‑as‑a‑judge/

[6] Pan, Q., Ashktorab, Z., Desmond, M., Cooper, M. S., Johnson, J., Nair, R., Daly, E., & Geyer, W. (2024). Human‑Centered Design Recommendations for LLM‑as‑a‑Judge (arXiv:2407.03479). arXiv.

[7] Bavaresco, A., Bernardi, R., Bertolazzi, L., Elliott, D., Fernández, R., Gatt, A., Ghaleb, E., Giulianelli, M., Hanna, M., Koller, A., Martins, A. F. T., Mondorf, P., Neplenbroek, V., Pezzelle, S., Plank, B., Schlangen, D., Suglia, A., Surikuchi, A. K., Takmaz, E., … Testoni, A. (2025). LLMs instead of Human Judges? A Large Scale Empirical Study across 20 NLP Evaluation Tasks. https://doi.org/10.18653/v1/2025.acl-short.20

[8] Luz de Araujo, P. H., Röttger, P., Hovy, D., & Roth, B. (2025). Principled Personas: Defining and Measuring the Intended Effects of Persona Prompting on Task Performance. (arXiv:2508.19764)

[9] Liu, Y., Iter, D., Xu, Y., Wang, S., Xu, R., & Zhu, C. (2023). G-Eval: NLG Evaluation using GPT-4 with Better Human Alignment (arXiv:2303.16634). arXiv.

[10] Chen, J., Lu, Y., Wang, X., Zeng, H., Huang, J., Gesi, J., Xu, Y., Yao, B., & Wang, D. (2025). Multi-Agent-as-Judge: Aligning LLM-Agent-Based Automated Evaluation with Multi-Dimensional Human Evaluation (arXiv:2507.21028). arXiv.